When an iconic figure dies suddenly and tragically, it can feel disorienting. On some level, we assume that celebrity, money, and fame insulate us from the realities of living. If only we can reach a certain level of success, we can protect ourselves and our loved ones from pain, grief, and even death.

Last week’s helicopter accident that caused Kobe Bryant’s tragic death left a handful of families with unimaginable pain and resonated globally with fans and admirers who mourned these devastating losses. These are difficult truths, and it can be appealing to put distance between us and those directly affected by denying that loss is everyone’s birthright.

For parents, I think there was another unsettling layer to this tragic accident: that Kobe Bryant’s 13-year-old daughter died alongside him. It feels wrong to register these words, to contemplate the death of a child. When I heard about the accident, I was traveling home from a conference in San Francisco; I hugged my sons tightly as soon as I walked through the door, confirmed their existence. They were there, present and whole; this simple credo is all we can hope for, and it is everything.

As parents, we are governed by the need to put our child’s needs first. We are pulled toward their gravitational force; our lives are organized by their very existence. We protect their vulnerable small selves, and we choreograph a dance of closeness and distance as they grow older and redefine the ways they need us. In order to move through each day, we must tamp down our worries about our children’s well-being and assume all will be well.

This delicate balance of worry and confidence allows us to cherish each day with our loved ones while not being overprotective or hampering their necessary growth towards independence and away from us. We navigate this balance habitually each day, so when forced to reckon with the tenuousness of life, it can feel crushing and raw, if we allow it—and we must allow it if we want to experience the full range of human existence. Being able to experience and understand this range is what enables us to make the world better for ourselves, our children, and their children.

When our children are born, we are so full but also a little emptier, as we move aside to make way for the next generation. When you have a child, they become the most valuable thing in the world, presenting us with the profound gift of seeing people clearly and understanding human value in an unvarnished, primal way.

Psychologist Allison Gopnik upends the model we assume governs our parenting: she asserts that we are not just capable of caring for people because we love them; rather, “love is engendered through caring.” It is by unselfishly caring for our children that our love for them evolves. When we care for our children, we sacrifice our own ends to allow them to do the things they need to do to find their unique way. This unselfishness leads to the deep love that can simultaneously scare and animate us. When we can care about children collectively—as parents, as educators, as advocates, and as a society—we have the power to change the world.

Caring for vulnerable people (and make no mistake: we are all vulnerable) is the ultimate act of kindness, and it can serve as a model for our ethics and our politics, if we will let it. What if, the next time we see an acquaintance on social media express a political view that does not reflect our own, we reach out to them privately to express curiosity in a respectful way? What if, instead of reacting with anger to a perceived wrong, we instead respond empathetically, with the understanding that the person who wronged us is vulnerable, and we are, too?

We know how to continue loving other beings across lines of disagreement and difference. We are capable of loving without getting something in return; for the sake of humanity, we must keep this certainty front and central.

I don’t know much about Kobe Bryant, but I am struck by the ways he was able to transform himself through reflection and giving of himself and his resources to others. He was a source of hope and a symbol of community. He sought to bring people together.

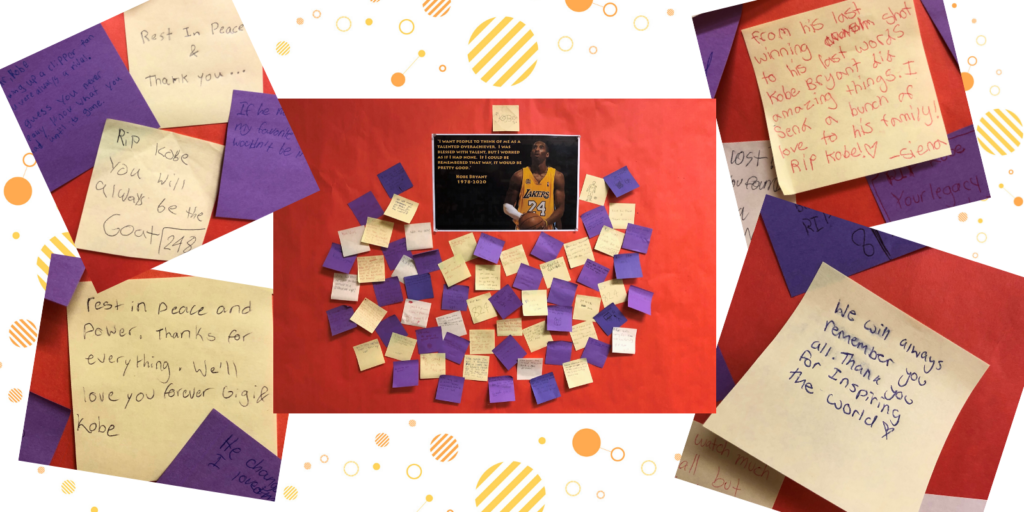

People loved Kobe because he cared. And I have seen proof of this around campus this week—students of all ages wearing their Bryant jerseys, the #24 sketched carefully in notebooks and folders, conversations on the field during recess, and in the incredibly touching memorial our Middle School students organized last Friday. We need more sources of cohesion, in our culture and our communities, that stitch us together across fractured lines of disagreement.

Our children keep us human. Relinquishing our egos and honoring them and their unique paths—despite our anxiety, our investments—are among our most sacred responsibilities.

Warmly,

Laura

Laura Konigsberg

Head of School

lkonigsberg@turningpointschool.org