Over Winter Break, I found some time and space to immerse myself in the books on my bedside table and enjoy the pleasure of sustained and effortless engagement with new ideas, sensibilities, and imaginations.

Over Winter Break, I found some time and space to immerse myself in the books on my bedside table and enjoy the pleasure of sustained and effortless engagement with new ideas, sensibilities, and imaginations.

Essayist and author Maria Popova asks, “How is it that tiny black marks on a white page or screen can produce such enormous ripples in the heart, mind, and spirit? Why do we lose ourselves in books, only to find ourselves enlarged, enraptured, transformed?” This sentiment resonates deeply with me, and I was grateful to reconnect with this powerful alchemy.

During the past few years, rapid information-gathering has taken precedence over the slow and blossoming self-knowledge that reading invites. You may have found yourself catching and deflecting bytes of knowledge at the expense of really being absorbed in feeling what it is to be human.

Marcel Proust said, “Reading is at the threshold of our inner life; it can lead us into that life but cannot constitute it… What is needed, therefore, is an intervention that occurs deep within ourselves while coming from someone else, the impulse of another mind that we receive in the bosom of solitude.” In other words, we learn about our innermost selves when we incorporate an author’s wisdom to develop our (own) inner perspectives and sensibilities.

Marcel Proust said, “Reading is at the threshold of our inner life; it can lead us into that life but cannot constitute it… What is needed, therefore, is an intervention that occurs deep within ourselves while coming from someone else, the impulse of another mind that we receive in the bosom of solitude.” In other words, we learn about our innermost selves when we incorporate an author’s wisdom to develop our (own) inner perspectives and sensibilities.

Without this deep relationship with others who bring us to the “threshold of our inner life,” we risk further alienation (from ourselves), an erosion of our sense of community, and difficulty thinking deeply and weighing information responsibly. Our very humanity is compromised.

We want the best for our children but cannot serve as role models for them if, in this key area, we miss the beauty of connecting deeply with ourselves and others.

Reasoning, thinking critically, communicating clearly, and cultivating empathy are all predicated on developing sustained attention. In a very short time, as our attention has been splintered, the way our brains are shaped to think about the world has noticeably changed. While thinking quickly in critical moments is a survival technique, it is not a tool we want our children to use daily as they navigate through life.

Reasoning, thinking critically, communicating clearly, and cultivating empathy are all predicated on developing sustained attention. In a very short time, as our attention has been splintered, the way our brains are shaped to think about the world has noticeably changed. While thinking quickly in critical moments is a survival technique, it is not a tool we want our children to use daily as they navigate through life.

If we wish to educate and equip our children to meet the unknown with the best tools available, we must cultivate strategies that can enhance our attention and ability to think deeply.

Recently, I listened to an interview with UCLA Professor of Education Maryanne Wolf and was fascinated to learn about the act of reading and that different kinds of reading affect and shape our brains differently.

Recently, I listened to an interview with UCLA Professor of Education Maryanne Wolf and was fascinated to learn about the act of reading and that different kinds of reading affect and shape our brains differently.

We tend to think that reading is a singular act and skill. But reading is a process with multiple systems and stages. The most common surface skill is decoding, when children understand the squiggles on the page as connected to language. As children practice reading, they build on that basic “circuit” (simply reading the words on the page) to glean basic information about a subject’s content. Reading for information is the most primitive basic level of reading that we engage in. Still, there are many more levels of depth involving taking on another’s perspective, or what Wolf refers to as developing a “theory of mind.”

In a world of screens, social media, and a constant stream of information, it becomes necessary to skim the surface. But when we don’t allow ourselves to slow down and process deeply, we miss the opportunity to consolidate our comprehension of what we’re reading.

Our “elastic” brains adapt to the ways we’re reading, so it’s no surprise that after several years of scanning headlines for information (exacerbated by the ever-shifting landscape of the world the past few years), we’re strengthening our amygdala’s “flight, fight, or freeze” mechanisms, all of which eschew attention or reflection in the name of survival. Our brains have become adept at reading quickly and then moving on to sample the next bite/byte of information.

Our “elastic” brains adapt to the ways we’re reading, so it’s no surprise that after several years of scanning headlines for information (exacerbated by the ever-shifting landscape of the world the past few years), we’re strengthening our amygdala’s “flight, fight, or freeze” mechanisms, all of which eschew attention or reflection in the name of survival. Our brains have become adept at reading quickly and then moving on to sample the next bite/byte of information.

Skimming is a useful skill, to be sure. But it comes at the cost of remaining in what Nicholas Carr coined “the shallows,” where we are unable to engage in deeper, more time-consuming work. In a distraction-saturated world, we are deterred from paying attention. Even if we, as adults, learned to read in a print format, consuming information in the ubiquitous digital format has rewired our brains, and it is more difficult to switch back to reading more deeply. It feels less rewarding.

In our digital world with vast information at our fingertips, we and our children face a level of stimulation that has the potential to undermine our ability to concentrate and dilute our ability to comprehend, evaluate, and remember information. When we accelerate toward the end of a digital article, we might move too fast to monitor our comprehension.

However, it is never too late to retrain our brains to rediscover the ability to deepen our reading and expand our ability to let information meaningfully sink in.

This means dedicating time to reading something challenging enough to take you out of yourself and to find beauty or empathy or those “a-ha” moments of transcendence. It’s the act of reconnecting with our “inner sanctuary” through books, music, or film—anything that transcends reality—and with yourself as a thinker with “a heart and a mind and a soul,” and of fostering this process in your children. It also means developing what Wolf calls a “biliterate brain” conversant in print and digital media.

This means dedicating time to reading something challenging enough to take you out of yourself and to find beauty or empathy or those “a-ha” moments of transcendence. It’s the act of reconnecting with our “inner sanctuary” through books, music, or film—anything that transcends reality—and with yourself as a thinker with “a heart and a mind and a soul,” and of fostering this process in your children. It also means developing what Wolf calls a “biliterate brain” conversant in print and digital media.

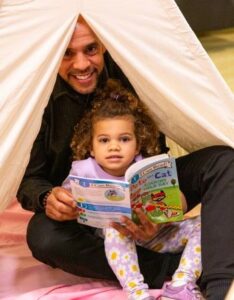

Wolf recommends reading every day to toddlers and young children learning to read from print books with reduced distraction on your part (i.e., put your phones away). Research shows that interactive reading with emerging readers strengthens their ability to understand the story by scaffolding the process of creating images. Audio reading was “too cold”: children had to work too hard to create images; animated versions were “too hot”: children had too much work done for them, so they lost the ability to develop them themselves.

In addition to the emotional bonding and physical closeness of parents/caregivers reading to their child, researchers found increased connectivity in children’s brains between and among the networks of visual perception, imagery, and language.

For most neurotypical children aged 5-10, print reading should be the main medium. But children at this age can learn programming and coding in digital formats simultaneously with reading in print [and may benefit from it in some cases]. As children get older, they learn and practice deep reading processes, critical analysis, and empathy. We should be guided by purpose when discerning why we might use digital or print materials for a particular task.

For most neurotypical children aged 5-10, print reading should be the main medium. But children at this age can learn programming and coding in digital formats simultaneously with reading in print [and may benefit from it in some cases]. As children get older, they learn and practice deep reading processes, critical analysis, and empathy. We should be guided by purpose when discerning why we might use digital or print materials for a particular task.

I hope my own experience reconnecting with reading as an expansive and soul-nurturing exercise might inspire you to think about how you might carve out time and space for this wonderful gift—and encourage your children to do the same. Prioritizing the act of reading deeply is a gift of connection we can give ourselves, our children, and each other.

Warmly,

Laura

Dr. Laura Konigsberg

Head of School

lkonigsberg@turningpointschool.org