This week’s blog is written by Ms. Katie Sibley, Turning Point School’s Student Learning Support Coordinator

It’s a Monday night and you’re making dinner in the kitchen when your daughter asks you where her cleats are because she needs them for soccer practice tomorrow…

At the same time, you’re thinking about how you’ll have to reschedule your doctor’s appointment on Wednesday because you won’t have enough time to make it from Santa Monica to Culver City for an event at school that evening…

Just as you are typing a reminder into your phone, your son comes up to you with his book and asks you what the word “veto” means…

You try to think of how to explain it in a way that a seven-year-old would understand…

Meanwhile, you’re trying not to lose your cool because you realized that you forgot to defrost the chicken you planned to cook for dinner…

It almost seems like a miracle when, at the end of the day, the soccer cleats are packed, the appointment has been rescheduled, veto has been defined well enough, and dinner is on the table (even if it is spaghetti, not chicken).

We have our executive functioning to thank for having the ability to multitask when necessary, plan ahead, get back on track in the wake of unending distractions, and display self-control through the many twists and turns in our days. Children need to develop these skills, too, in order to become successful students—from preschool to graduate school—and, eventually, productive and efficient adults.

What is Executive Functioning?

Often executive functioning is referred to as the CEO, the air traffic controller, or the director of the brain. It is because of executive functioning that we are able to get anything, and I mean anything, done.

Often executive functioning is referred to as the CEO, the air traffic controller, or the director of the brain. It is because of executive functioning that we are able to get anything, and I mean anything, done.

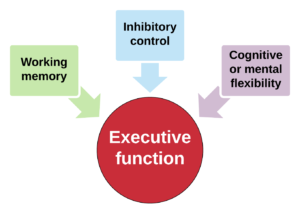

Executive functioning is an umbrella term for three basic cognitive abilities:

- Working memory – the ability to hold information in our mind and use it

- Inhibitory control – the ability to control thoughts and emotions, like resisting distractions and controlling impulsive behavior

- Cognitive flexibility – the ability to switch gears to adjust to changing demands, perspectives, and priorities

Therefore, executive functioning is responsible for a number of skills including:

- Paying attention

- Organizing, planning, and prioritizing

- Starting tasks and staying focused to completion

- Shifting/transitioning to new tasks

- Understanding different points of view

- Keeping track of materials

- Time management

- Self-monitoring (keeping track of what you’re doing)

- Regulating emotions

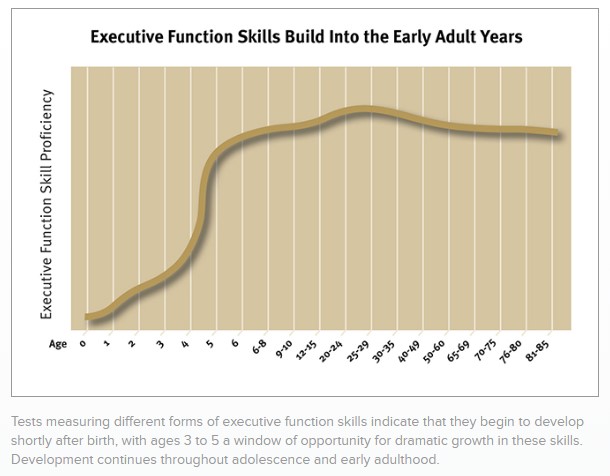

Brain development is not something we only pay attention to in infancy and early childhood. Full brain development takes approximately a quarter-century, and as our brains develop they do so from back to front. The area of the brain where executive functioning resides is the prefrontal cortex. Located right behind your forehead, the prefrontal cortex is the very last part of the brain to fully form.

It’s no wonder children and teens struggle with organization, focus, and regulation. And even as adults, we certainly still have executive functioning challenges from time to time—the difference is that we have a mature, fully-formed executive functioning system to help us sort out challenges.

Graph Credit: Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University

When working with our students and children, we have to be careful that we’re not putting our adult expectations of executive functioning onto their still-developing executive functioning systems. While it can be very hard to understand why your child isn’t turning in the homework that they have spent time doing, or why they’re not chipping away at a long-term assignment a little bit at a time, we have to remember that that is not yet how their brains are wired. What we can do is support them at school and at home to better develop these skills as they grow and mature.

What do we do at school to support the growth of executive functioning skills?

At Turning Point, we recognize that all students, in varying degrees throughout their schooling, benefit from explicit instruction around executive functioning. Teachers, as we all know, do more than purely deliver academic information to their students. One of the myriad ways they foster growth in students is through the instruction and practice of executive functioning skills.

Here is a glimpse into some of the ways we, at Turning Point, support the development of executive functioning:

Self-regulation strategies build students’ self-awareness about how they’re feeling, or “how their engine is running.” Teachers help identify strategies and then work with students on what strategies will help to get them back to “just right.” This could be through a Brain Break, some movement like wall push-ups, non-punitive time in a Quiet Corner or Refill Station, or mindfulness activities.

Self-advocacy is speaking up for what you need to be successful. We encourage all students to communicate with their teachers if they need more support or if they need a break.

Routines are predictable and practiced ways of doing daily activities. Students follow the same procedures every day for things like walking in the halls, caring for materials, arriving prepared for class, and writing down and turning in homework. Routines at school help students to internalize a rhythm for how things are done effectively and efficiently.

Goal setting helps students to identify the many little concrete steps they can take to help achieve their bigger, more general goals.

Chunking information means teaching students a skill or lesson and then giving them a chance to practice it and reflect on it, before adding on a new skill. This is built in to the structure of our lessons, which all begin with a mini-lesson and then give students an opportunity to digest and integrate the new knowledge with independent or small-group practice.

Timers of all kinds help students effectively use smaller amounts of time and can be great motivators for some students. It also builds awareness around time, for example, “How does one minute feel? How does five minutes feel?”

Breaking longer assignments into smaller, more manageable pieces helps students tackle what could be an overwhelming project by identifying mini-goals within the larger context. Teachers often break assignments down with students in order to model the practice, so that students can eventually perform this function on their own, in many different areas of their life.

Checklists and rubrics both help students see what pieces they need to complete and what their teachers are looking for in their final product. Clear expectations help steer students on the right path.

Planners and the Student Portal on Veracross provide older students with resources for referencing their assignments and upcoming projects, quizzes, and tests outside of school. Having their work digitally on Veracross and Google Classroom not only reduces paper waste but also reduces the risk of papers getting lost.

Study skills and aspects of executive functioning and the brain are taught explicitly by teachers in the higher grades. Students work with the teachers to keep their binders organized and cleaned out, plan for upcoming assignments, and build awareness around time management by looking at weekly and monthly calendars. By learning and practicing different study strategies, students are eventually able to take ownership of their learning.

Reflecting and monitoring give students an opportunity to evaluate the quantity and quality of their work. Many teachers ask students to complete reflections after they’ve completed an assignment with questions such as, “What went well for you on this assignment? What was challenging for you? What would you do differently next time?”

What can you do at home to support the growth of executive functioning skills?

As we know from reading Brain Rules by John Medina, the foundations of healthy brain growth are simple: enough restful sleep, nutritious foods, and exercise. There are some additional things you can do with your child to help build their executive functioning skills, like:

As we know from reading Brain Rules by John Medina, the foundations of healthy brain growth are simple: enough restful sleep, nutritious foods, and exercise. There are some additional things you can do with your child to help build their executive functioning skills, like:

Routines, at home like at school, help children to know what to expect and help them to stay regulated and balanced. A designated and consistent study or homework space and time (that your child helps decide upon and create) is another great way to provide structure with some ownership. The space should have limited distractions and all the supplies needed to complete homework.

Timers can help children stay on track and build an awareness of the passage of time.

Mindfulness at home can help children understand and regulate their emotions.

Games that practice executive functioning skills like working memory, planning ahead, flexible thinking, self-control, and strategy are a great way to “sneak in” executive functioning skill-building in a fun, family-friendly way. Some examples of these games are Memory, Uno, Jenga, Distraction, Spot It!, and Battleship. For more game ideas, click here.

Modeling your planning and thinking can really help children see that executive functioning skills are a part of all of our everyday lives. Some examples of language you could use are:

- “I have a hard time keeping all these dates straight in my head so I write them down in my calendar.”

- “I’m feeling tired but it’s not time for bed yet. I think if I go for a little walk, that will wake up my brain and body.”

- “I’m feeling overwhelmed, so I’m going to pause and take a few deep breaths to make myself feel ready for whatever comes next.”

- “The way I usually solve this problem isn’t working, so I’m going to try another way.”

- “This is not something I love doing, but I know it is important. Maybe if I do it now, I can do more enjoyable things later, and feel good about getting it out of the way.”

In closing, I want to tell you about an interaction I had with a second grader this week. “Ms. Sibley,” she beamed, “yesterday I got home and did my homework without my mom even telling me to do it!”

I asked her what had motivated her to do her homework and she said, “I had to do it right after school because later I had horseback riding and then when I get home I’m too tired.”

When I asked her how it felt to make that decision on her own, she replied with a huge smile, “I got everything done and my mom was so happy!”

It was like I could almost see the connections lighting up on her forehead, illuminating real growth happening underneath the surface in her prefrontal cortex. She had planned, managed her time, initiated, and completed her work independently. She had the satisfaction of a job well done and she received positive feedback from her parent that served to reinforce her choices and behaviors. She is on the right track for developing executive functioning skills.

Don’t worry, however, if you’re not hearing your child make those kinds of decisions yet. Remember, their brains are working hard to get there, and we need to honor and support their unique process and the pace of their development.

I am including a couple of resources below that will be helpful for those who want to take a deeper dive. I am also always happy to share ideas and hear what has worked for you and your family, so please don’t hesitate to reach out!

Katie

Katie Sibley

Student Learning Support Coordinator

ksibley@turningpointschool.org

Additional Resources

- Key Concepts about Executive Function & Self-Regulation

- Enhancing and Practicing Executive Function Skills from Infancy to Adolescence

Credit: Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University

———————————–

Head’s Corner Blog is Published by:

Laura Konigsberg

Head of School

lkonigsberg@turningpointschool.org